A Tale of Two Telephones:

Competitive

Telecommunications in Early 20th Century Montana

Óby Dan Elliott

Unabridged

Account especially for DialMontana.com

May 8 with May

28 revisions--2012

“Do you know,

have you had occasion to learn, that there is no hospitality for invention

nowadays? There is no encouragement for

you to set your wits at work to improve the telephone, or the camera, or some

piece of machinery, or some mechanical process; you are not invited to find a

shorter and cheaper way to make things or to perfect them, or to invent better

things to take their place. There is

too much money invested in old machinery; too much money has been spent

advertising the old camera; the telephone plants, as they are, cost too much to

permit their being superseded by something better. Wherever there is monopoly, not only is there no incentive to

improve, but, improvement being costly in that it ‘scraps’ old machinery and

destroys the value of old products, there is a positive motive against

improvement.”

President

Woodrow Wilson in “The Emancipation of Business”

(The World’s

Work, June 1913, vol. 26, p. 185)

Prologue

The first telegraphic dots and dashes in Montana were heard tapping

at its territorial capital of Virginia City in 1866. This three-decade-old marvel, the reigning gold standard for

fast, longer distance communication, famously was initiated with inventor

Samuel Morse’s message “What Hath God Wrought!”. A telegram was a much faster, less private version of millennia

old letter correspondence received or sent by mail carrier, although most often

it would be impersonal, abbreviated and reserved for important matters. Like

mail correspondence, a telegram didn’t barge into one’s home from the ethos as

an uninvited electronic visitor --- it properly was hand delivered at the front

door. Telegraphy was a comprehensible,

significant first salvo in establishing a new communications paradigm: it imbued residents in remote places like

Virginia City with a current sense of the world afar, and it gave birth to an

electronically-based age in which people would expect a new wealth of more

information, much more quickly.

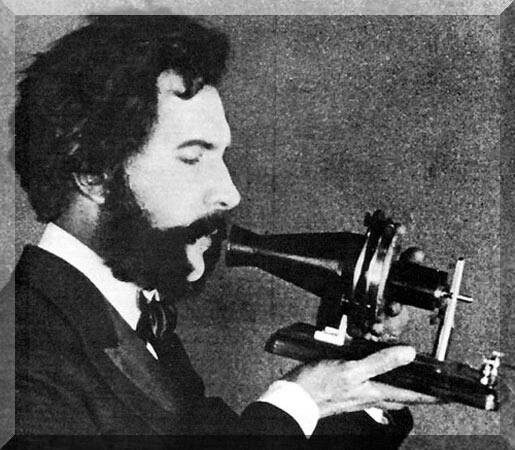

This matter of expectation soon would change again starting just a

decade later in America’s centennial year when the telephone was patented. It would transform the leap in

communications started by the telegraph into a new interactive information age: Its frequent long distance communications

were practiced within one’s home, in real time, by interacting and natural

sounding virtual voices. It was a

tool in which inventors took another decade initially to explore, and at least

that long for the public to become somewhat acclimated. Meanwhile, capitalists and corporate

executives were devising strategies for its profitable use, beginning in the

Age of Empire and extending into the cusp of the Populist and Progressive

periods.

The account following features a brief supercharged subset of

these periods in which competitive telephony would prevail in Montana at the

beginning of the 20th century from 1907-1912---just after Bell’s original telephone patents had expired late in the

19th century. The story begins with a

strong competitive push that quickly resulted in significantly more

telecommunications in Montana, some of it on the cutting edge for the

time. It unwinds unfortunately when

competition is squelched...and monopoly resurrected. The deconstruction begins with corporate overextension,

shenanigans and deceit. Ultimately,

main actors in this tale claim the dubious distinction of being named principle

defendants in the first ever antitrust action brought by the U.S. government

against the telecommunications industry.

An unintended consequence for seventy ensuing years, after quick

settlement of the litigation, was the attenuated development of the information

age in America and Montana.

A Terse Introduction to Automatic

Telephony, and Our Main Character

Less than a month after President Cleveland signed the Montana

statehood bill on February 22, 1889, a Kansas City undertaker named Almon

Strowger filed his patent application on March 12th for the first automatic

telephone switch. The new patent was

approved two years later—just a couple of years before Ma Bell’s original

telephone industry patents were set to expire. (Source: 2) (Link to Footnote A) A1

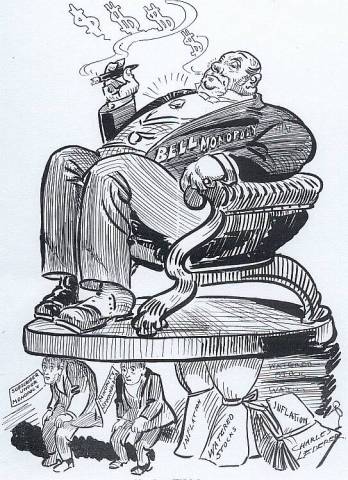

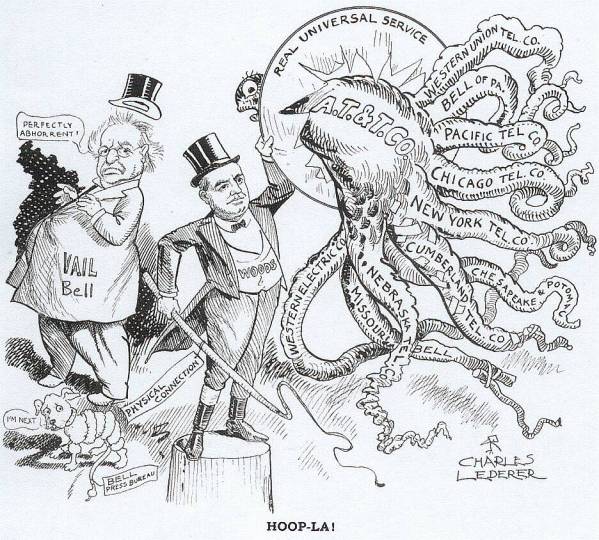

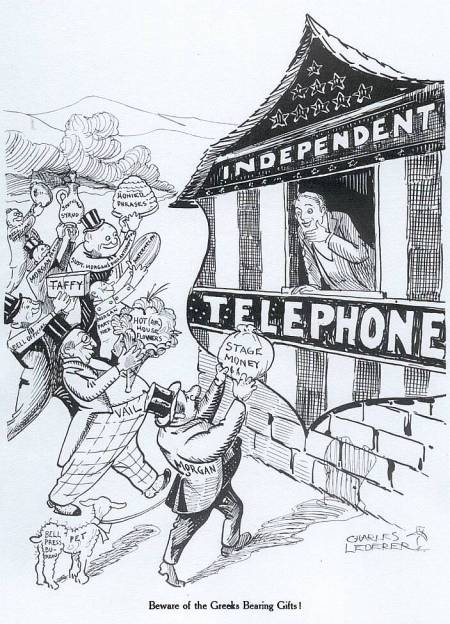

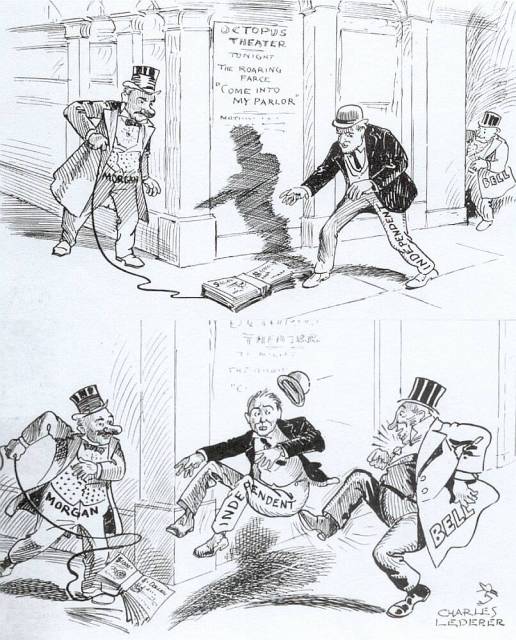

Telephone service had been provided for a dozen years prior by the monopolistic Bell system, also known as “Bell” or eventually the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (ATT), or, with no love lost, nicknamed the Octopus. Why? Because its tentacles were into everything even tangentially related to providing telephone service: Politics, court cases, franchises, newspapers, you name it, they were involved. (Below is one depiction of the Bell monopoly of the day.)

The Bell organization was comprised of a federation of local

exchange companies (in Montana known as the Rocky Mountain Bell Company or

RMBC), long distance toll operations connecting the local exchange companies

and equipment operations. The regime

knew it would face competitive headwinds with the expiration of Alexander

Graham Bell’s original telephone patents in 1893-94, and it had planned

accordingly, as we shall see. These

years of economic depression saw the telephone industry in America thrown open

to twenty years of competition, sometimes knuckle-hard, which resulted in

innovation and significant expansion of areas being served and customer

numbers. (Learn more about the history of the Bell System at this link: Bell System Sidebar) BSS

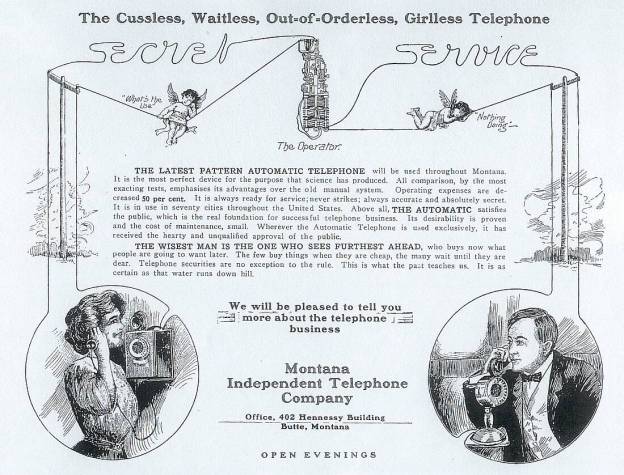

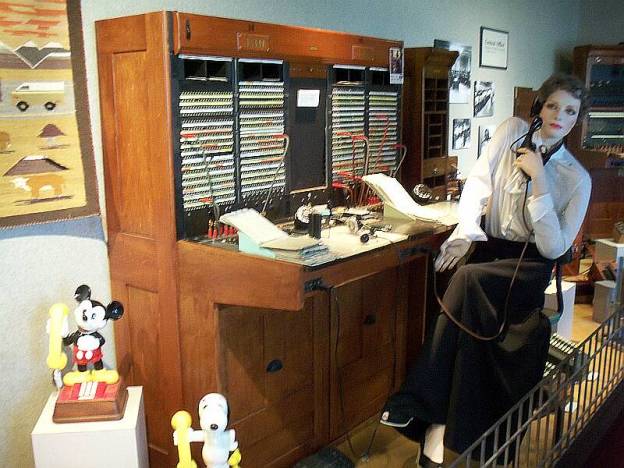

Strowger’s automatically switched local calling, and the dial

telephones complimenting it, would play a key role in this new competition,

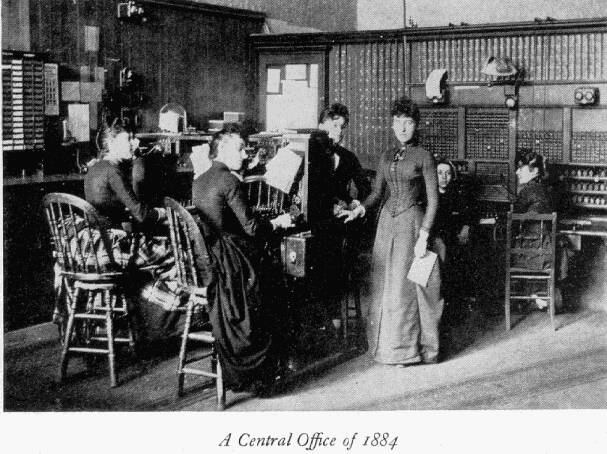

innovation and expansion. His automatic

switches, compared to the manually switched operator-based calling of Bell,

were advertised to be “girl-less, cuss-less, out-of-order-less and

wait-less”. These words resonated with

meaning to the consuming public because callers were connected much more quickly,

calls were confidential and callers were relieved from having to interact every

time they placed a call with a third party, that being one or more

unpredictably impersonal, arbitrary or even pernicious, sometimes cutesy,

perhaps too curious, over-worked and inadequately compensated operators. In fact, an operator intentionally

connecting callers with his main competitor’s undertaking business spurred

Strowger to invent the automatic exchange switch; the operator was his

competitor’s wife. (Source: 2)

Within a dozen years, the company producing Strowger’s invention,

the Automatic Electric Company (AEC), was operating a six-story headquarters

and manufacturing plant in Chicago. Its

early 20th century automatic switching and dial telephone products were

tailored for sale to newly emerging Independent telephone companies

constructing local exchanges in their attempt to compete with Bell’s older,

less economic technology. So how did

this affect Montana? We’ll first need

to visit Ohio and New York. (Source: 3)

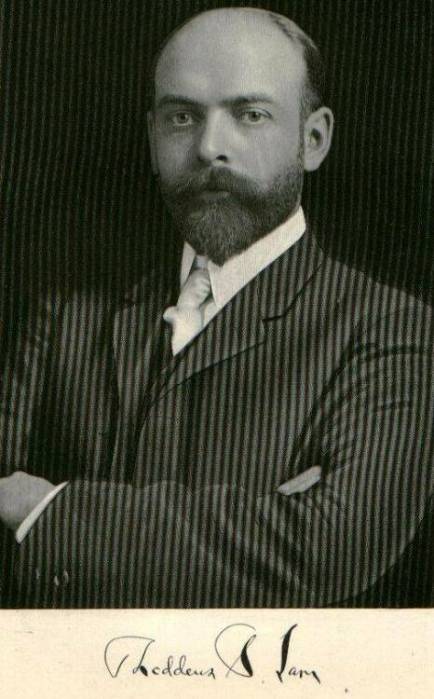

It was in the dawning of the 20th century that a bright young

entrepreneur named Thaddeus S. Lane began developing his skills in the newly

competitive telephone industry. He was

born on a Gustavus, Ohio farm on February 10, 1872 to Truman M. and Melissa

Lane, hearty descendants of colonial America who drove an ox team to the rural area. After high school, Thaddeus taught school

briefly before taking a job in telephone manufacturing. His marriage to Miss

Lilian Payntar at New York City in 1897 soon produced one daughter,

Lilian. With his native talents still

undeveloped but in the ready, the stage was set for Thaddeus. One may wonder how this modest beginning

would lead him to embark on a highflying career befitting the era’s cleverest business

elite, but that is indeed what would occur. (Sources: 5, 64A)

Thaddeus Lane’s manufacturing experience led him, with three other

Ohioans, to apply in 1901 for an Independent telephone company franchise at the

town of Jamestown, New York. The

Independent local exchange would compete with the Bell system. Within two to three years his Independent

telephone operation, the Home Telephone Company of Jamestown, effectively was

rivaling Bell operations in the area.

Part and parcel of successfully competing with Bell inevitably involved

skirmishes with its well-oiled publicity machine. As Lane’s prominence grew, so did the size of his target. (Source: 6)

Bell’s early 1904 publicity campaign in over a dozen New York

newspapers targeted N.Y. Independents, including Lane. His response in the Jamestown newspaper was

reprinted in the national journal Telephony in February 1904. In it he demonstrated his gift of logical

expression often used to hoist an opponent by his own petard, his understanding

of Bell’s tactics and his first mention of Montana telephony: “A few failures of Independent telephone

companies are noted, although to find them the Bell company has been obliged to

go as far west as Montana and as far south as Georgia. Some of these failures have been advertised

by the Bell company no less than thirty-seven times, from which it would appear

that material for this style of advertising is somewhat scarce. It will be noted that the Bell company, in

its advertising, makes no claims of superior service, but on the other hand

confesses that it has not been equal to the occasion: has not been able to meet

competition, and has permitted its competitors, the Independents to occupy and

develop territory in many sections of the country driving the Bell company

entirely from the field.” (Pictured

below is the generic Independent Telephone Association logo.) (Source: 7)

(Link to Footnote B) B1

Although Mr. Lane’s New York operations were located in a

competitive Independent company v. Bell system hotbed, by 1906 he had expanded

and was thriving as an owner, director or manager of forty-two telephone

exchanges, secretary of the New York Telephone Association and delegate to

International Independent Telephone Association conventions. He was well connected in the avant garde of

the burgeoning Independent company industry, even in a broadly regional,

perhaps national way. (Source: 8)

Transition to

Montana

This notoriety, which had garnered the attention of a leading (but

unidentified) Butte citizen at some important juncture, would have significant

consequences for Mr. Lane, and Montana.

The Buttian had attempted in early 1906 to call long distance over RMBC

lines, Salt Lake City to Butte. When

billed for this call that was never connected, the man repeatedly refused to

pay, that is, until RMBC threatened to terminate his telephone service in

Butte. This irascible incident resulted in a Butte brainstorm: Bell in MT

needed a good lick of competition. The

man, with quick dispatch, contacted a bright, aggressive and young New York

acquaintance: Thaddeus Lane. After

“conferences” with Butte businessmen, the adroit Mr. Lane “was induced to come

to Butte”. (Source: 9)

Timing in 1906 for a move to Butte would be propitious for T.S.

Lane. A brouhaha of sea-changing

proportions was playing out in New York between large moneyed, but poorly run

and nearly defunct Independent telephone interests, and even larger moneyed

Bell interests. New York’s attorney

general had pushed Bell interests from the catbird’s seat by exposing a

secretly proposed anti-competitive sale of the Independent company properties

to a Bell intermediary. Bell had lost

the round, but so had the Independents because their big eastern money-center

financiers significantly were vested in the large, strategic sale. A lingering, deleterious effect on

Independent companies across America was a narrower choice of financing options

from which to choose; even watered stock and ponzi schemes would be used---this

requirement would affect Montana.

Whether he intended it, Lane’s operations had been ensnared in the

peripheries of the bruising match, with local investors assuming a controlling

interest in the Jamestown Home Telephone Co.

Indeed, it was a good time to “Go West, Young Man”. (Sources: 10A, 10B,

10C, 10D, 10E, Horace Greely)

Also fortuitous for T.S. Lane as he arrived at Butte were two

Montana Supreme Court cases clarifying governmental requirements for new

telephone companies desiring to operate within cities and towns. In Rocky Mountain Bell Telephone v. Mayor of

Red Lodge and Crumb v. City of Helena, March 26, 1906, the Court overturned as

unconstitutional the 1905 Legislative enactment that excluded rights-of-way

within cities and towns from the statewide requirement allowing utility

construction in rights-of-way. With these decisions, municipalities were

obliged to grant franchises to potential new competitors like Mr. Lane, if they

could provide a modicum of proof that they were capable of providing

service. (33 Mont 45, 34 Mont 67)

The Crumb in the Helena case was the W.H. Crumb Company of

Chicago, a telephone equipment manufacturer.

It was Crumb’s intent at the time of the court case to construct

exchanges in Great Falls, Helena and Bozeman, with another Independent company

to operate in Montana cities further south and west. However, company owner W. H. Crumb found himself subsequent to

the courts decision to be enmeshed in the corrupt telephone politics in

Chicago, a situation in which he found common ground with the vortexual Bell

interests. His quest to build

Independent company exchanges competing with Bell interests in Montana clearly

had lost its lustre. That meant Mr.

Lane’s fortunes out west could include not just Butte, but potentially a large

swath of Montana. (Pictured below is

the dapper Thaddeus Lane.) (Sources:

11A, 11B, 11C)

The very next month following Crumb, Thaddeus and several others

organized the Montana Independent Telephone Company (MITC). Authorized capitalization was $1,500,000 in

6% bonds and common stock of the same amount; papers of incorporation were

filed May 12, 1906. The city council

took only two weeks to approve its franchise.

Twenty Montana business leaders immediately subscribed to the securities

at $5,000 each. Even F. Augustus

Heintze, one of the copper kings, was interested, although the strength of his

finances was in sharp decline.

(Sources: 8, 9, 12A, 12B, 12C, 26) (Link to Footnote C)

C1

The initial investors and directorate of MITC included T.S. Lane,

who was in charge of construction, a cadre of well-known Butte bank presidents,

Con Kelley of the Anaconda Company, P.B. Moss of the Billings First National

Bank, W.G. Conrad and Thomas Couch, Jr. from Great Falls, Harry Gallwey of the

Parrot Mining Company, and Elmer Jones of the Utah Independent Telephone

Company. Soon to be included were John

MacGinniss, a Butte banker and Heintze confidant who had married into the

family of copper king W.A. Clark’s brother, and former State Auditor and

railroad capitalist, A.B. Cook of Helena.

These last two men with Lane would form the nucleus triumvirate of

future dealings, some of which would become top-drawer machinations of the era. (Sources: 13B, 14A, 14B, 14C)

Sophisticated

Strategic Planning I

Part and parcel of MITC’s formation was another company organized

by Lane and a few directors one month later on June 16, 1906: the Inter-Mountain Construction

Company. Its formation was a

significant lynchpin as Lane planned construction activities in Butte, as well

as a wider expansion into other Montana communities. A separate construction company could provide flexibility to

segregate messy construction liabilities and activities away from the balance

sheet of the telephone company. Raising

money from small subscription investors in which early generation investors

could be (and often were) paid by subsequent generation investors (a ponzi

scheme), if done by the construction company, ostensibly would not tarnish the

telephone company’s reputation.

Completed facilities could be transferred to the telephone company, away

from construction company creditors.

Contract manipulation between the telephone company and construction

company would allow very substantial write ups in the values of telephone

company securities held by the construction company and its owners (and

corresponding plant value write ups on the telephone company balance sheet), as

well as the ability to extract several levels of profit margins from ongoing

contracts with the telephone company. If complexities arose, transfers of

funds, financing and other details back and forth between the telephone company

and the construction company easily could be accomplished with little or no

scrutiny. In short, telephone company

financials could be hyped as “conservative” and profitable, while construction

company financials and their potentially large profits would be hidden from

public view. Two more construction companies eventually would be formed: The

Western Engineering Company for Helena exchange construction and the Montana

Engineering Company for Great Falls exchange construction. (Sources: 16A, 16B,

16C, 16D, 28) (Link to Footnote

D) D1

A letter segment, Lane to Cook, is worthy of a thoughtful reading

because it demonstrates in Mr. Lane’s own words the financial finesse he coaxed

and cajoled between construction and telephone company financials. The telephone company name has been changed

to ‘X’ to assist in an easier to grasp understanding of where the pea is under

the shells: “In order that you,

MacGinniss and myself show six payments up to date, I can think of no other way

to arrange it except on the books of the Telephone Co. ‘X’ to credit each of us

with our payments and charge the Inter Mountain Construction. Co. The Inter Mountain Construction Co. will

show a debit against each of us for this amount, which must, in some way, be

repaid. It is not quite clear in my

mind just how to handle this, but perhaps the best way is to have the Telephone

Co. ‘X’ advance money to the Inter Mountain Construction Co., and the

Construction Company loan it to Cook, MacGinniss and Lane, and Cook, MacGinniss

and Lane pay it into ‘X’.” These

complex financial arrangements were classic early 20th century financial

obfuscation, complimented by the period’s lax accounting standards. The astute Mr. Lane mastered these practices

as a slick modus operandi --- lock, stock and smoking barrel. (Source: 17)

This kind of shenanigry may have comprised the building blocks of

titans in the Age of Empire, but the Populist and Progressive movements rooted within

average working folk in the early 20th century hotly resisted them. This especially was true in places like

Butte. Trust busting and threats of

public ownership of certain private corporations were in vogue, and gaining

traction. Muckraking, such as Paul

Latzke’s “A Fight With An Octopus” published in 1906, fueled a populist public

angst, in this instance against the competitor Lane would again face, the Bell

conglomerate. (Source: 9)

Latzke’s introductory summary at Chapter One heralds the sentiment: “The story of the Bell companies rise to

power that was second only to that of the Standard Oil Company—The betrayal of

friends and associates, the sacrifice of great national characters and the

desperate purpose of a fight that was carried straight into the White House—The

waning of the power of the trust and the triumph of the people.” The newly transplanted Mr. Lane would need

to exercise caution, and employ his personal charisma, to avoid being lumped in

with Bell as an abuser of the public trust in the rough and tumble Montana mining

camp.

It was against this backdrop that MITC planned local exchange

networks in Butte, Anaconda, Helena, Great Falls, Missoula and Dillon, along

with the purchase of existing local exchange networks, such as those in

Bozeman, Livingston, Billings and other small communities. Six of these in the

largest Montana communities (comprising most of the populace to be served)

would house Almon Strowger’s AEC automatic switches and use dial

telephones. The company over-optimistically

predicted a customer base of 10,000 within a year following initial Butte area

construction. (Sources: 15, 64A, 66, 67)

MITC’s plans for a

complimentary instate long distance toll system were in addition to the

local exchanges. The toll system would

interconnect the large communities just mentioned, and in so doing would string

together a multitude of small town local exchanges with manual switchboards and

up-to-date central battery systems, sometimes in leased buildings. With his

skills of persuasion and hearty embrace of the Independent company movement, Mr.Lane

also would be able to purchase small, relatively rural companies with little

more than securities of his own companies for payment. He thereby could create a synergistic

Independent toll system, an avenue perhaps not as palatable for Bell, given its

slow capital deployment in rural Montana. (Source: Stock certificate, 13B, 69,

65, 67)

Another long distance toll system, that being a rather grandiose multi-state

long distance toll system, were explained in a mid-1906 issue of the American Telephone

Journal: MITC would partner with the

Utah Independent Telephone Company, joining at Pocatello, Idaho. To the west, it would connect at Missoula

with the Home Telephone Company of Spokane.

Director Jones from Salt Lake City had arranged for the use of Western

Union telegraph poles, as well as various railroad rights-of-way allowing

eventual long distance toll all the way to San Francisco. (Source: 15)

A Constitutional

Wrinkle

A year later, these long distance toll plans could have been

modified pursuant to a July 1907 decision by Federal Judge William Hunt of

Helena, who upheld Montana’s unique constitutional provision requiring

telephone interconnection. The

potential importance of this provision and Hunt’s decision can’t be overstated. The constitution specified that any

telephone company had the right to connect its lines with those of any other

telephone company. The Montana

legislature had enacted provisions for this constitutional specification nearly

coincident in time with the expiration of the original Bell system

patents. (Sources: 1889 Constitution

Sec.14 Art.15; 1895 Legislative Code Section 4401; 155 Fed 207)

Recall from the sidebar discussion earlier regarding Bell’s

lynchpin long distance toll strategy: after the expiration of its patents, Bell

planned to isolate Independent company local exchanges from important big city

Bell local exchanges by refusing to let the Independents interconnect via ATT

long distance toll lines. In Billings

Mutual Telephone Company v. Rocky Mountain Bell Telephone Company, Judge Hunt

held that physical interconnection and right of use was compelled by

statute and the state constitution, and that damages were to be assessed as

provided under the Code of Civil Procedure if a “compensation” agreement for interconnection

couldn’t be reached. (Source: 16)

In 1907, only Montana, South Dakota and Texas had enacted specific

statutory language regarding interconnection, and of these three, only in

Montana was the statutory language buttressed by its constitution and an

affirmative decision in a Federal Court.

T.S. Lane could have opted to enter the Montana market with his advanced

local exchange automatic switching and dial telephones, and then used RMBC’s

long distance toll lines to interconnect his local exchanges. Even RMBC local exchanges could have been required

to interconnect with Lane exchanges.

Many Independent companies in other states agitated for this approach in

years to come, but they lacked the legal underpinnings available in Montana. (Pictured below is a physical

interconnection cartoon of the day, with one version of the Bell octopus.) (Source: 17)

Lane demurred from this approach; RMBC’s aging technology and his

plans to build his own synergistic toll system mentioned above may have been a

factor. More importantly though, the

shrewd Mr. Lane knew this critical issue with nationwide ramifications

undoubtedly would be bound up in court by Bell. Sure enough, after three years of further court proceedings,

Judge Hunt finally was able to appoint O.T. Crane, N.B. Holter and W.C.

Bruskett of Helena to determine the Billings “compensation” question for

interconnection. The 1907 victory for

Independent companies in Montana nearly had been laid to waste by RMBC’s legal

tactics. We shall see, though, that the

issue retained a spark of life. (Source: 18)

Other Planning

Considerations

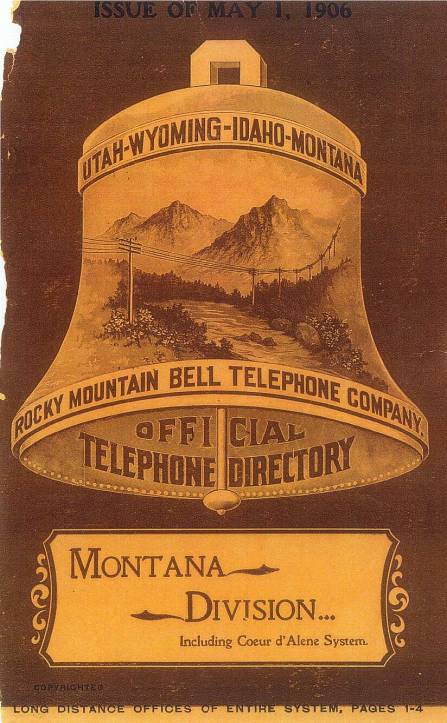

Evidence about the

competitor MITC would challenge can easily be gleaned from the May 1906 RMBC

telephone directory. It was a mere 6 ¼”

x 9 ¼” x 3/8” thick, a minimally sized book considering it included all Montana

customers in twenty-five local exchanges, and all customers in six Idaho

exchanges. Several instructions in the

book demonstrated RMBC’s spartan, nearly brusk approach to instructing the

public on how to use its operator-assisted technology:

--“Subscribers are requested to call only by number, and to

strictly avoid loud and boisterous conversation.” The first part of this instruction required customers to use the

telephone book, rather than asking operators to retrieve numbers. The second part dictated behavior. This instruction would be superfluous for

most of the customers served by MITC, with it preponderance of automatic

switching and dial telephones.

--“Subscribers are not permitted to allow non-subscribers to

use their telephones, such being in violation of their written contracts.” and

“Profane language over the wires is strictly prohibited. The Company reserves the right to remove the

instrument for violation of this rule.”

RMBC operators in the relatively small communities served in Montana

would have been able to monitor these behaviors as a kind of “big brother”,

while MITC’s cutting edge equipment

would protect most of its customers against such intrusion.

--“When it is desired to have a non-subscriber called into one of

our public offices at a distant place, a messenger will be sent for him, during

business hours, at the expense of the party ordering the service.” The telephone directory provides no further

guidance on the cost of the service, but “Messenger Boys” was advertised in at

least nine locations in just the Butte section of the thin directory. This service was convincing evidence of a

less-than-optimally served telecommunications market in Montana: it was

tantamount to delivery of a telegram.

MITC competition would begin remediating this situation with more

technologically advanced and less expensive service, thereby alleviating the

need to use “Messenger Boys”. (Sources:

104 and May, 1906 RMBC Directory)

(Pictured below is the cover of the May 1906 RMBC directory.)

Another competitive consideration was solved at the 1907

Legislative session, that being the unwillingness of railroad, express and

telegraph corporations to allow installation of Independent company telephones

in their stations. These entities

predictably didn’t care to facilitate competition of any kind. However, the issue was of vital importance

to the Montana Independent Telephone Company (MITC) because significant numbers

of local businesses absolutely needed telephonic communications with these

principle transportation and freight operations. Accordingly, Lane and his MITC supporters pushed House Bill 291

to successful passage. Its language

required all public railroad, express and telegraph stations and offices to

install or allow to be installed in every city and town served, a telephone

from each telephone exchange operating in the locality. Furthermore, it required promptness in

answering incoming telephone calls, as well as “correct replies to be made to

all reasonable and proper inquiries” made during business hours. Failure to comply was a misdemeanor. (Source: 80)

Labor unrest among Bell linemen and operator corps significantly benefited

the fledgling MITC in the midst of its Butte exchange construction when two

short strikes were waged, followed by a ten-month strike starting June 8,

1907. The strike would reduce Rocky

Mountain Bell Company’s (RMBC’s) customer numbers. As well, the effects of this strike spread to the Montana

Federation of Labor and Helena Trades and Labor Assembly, which ordered strikes

at businesses where Bell telephones were installed. In December, a mob of 300-500 dangerously drove six non-union

Bell employees from Butte, despite a restraining order issued by Judge

Hunt. The next February, Presidential

pardons were denied to Lenihan, who was past president of the Electrical

Worker’s Union of Anaconda, Plunkett, Shannon, Cutts and Edwards; each was

sentenced to 4 months prison time for violating Hunt’s order. (Sources: 19A, 19B,

19C, 19D, 77) (Link to Footnote

E) E1

Another city in which RMBC found discontent was Great Falls, the

home of MITC investors W.G. Conrad and Thomas Couch, Jr. In the spring, 1907 a large meeting of

citizens was held to adopt resolutions condemning Bell’s poor service, unfair

operator wages and high rates. One

account suggested that citizens unilaterally remove Bell company telephones if

a resolution solving their concerns wasn’t forthcoming. Red Lodge, Billings Livingston, Bozeman and

Lewistown also were hotbeds of labor discontent targeted at RMBC. (Source: 20)

Conjecture may lead one to assume that directors were fomenting

citizen discontentment in Butte and Great Falls. However, the business case alone was convincing since it rested

upon the precepts that the RMBC facilities and business model in Montana were

antiquated in a field evolving quickly with newer technology and lower

rates. In fact, RMBC average rates in

Montana were 20% higher than those in every other RMBC state---Idaho, Utah,

Wyoming and Eastern Oregon---with Butte and Helena having the highest rates.

The high rates persisted even though it was not unusual for used equipment to

be recycled into Montana from other RMBC states. As is many times the case, Montana would not be a recipient of

better technology and rates--that is, unless competition forced the issue. Beyond technology and lower rates was

another very basic issue: many Montanans simply didn’t have access to telephone

service at all, especially when compared with the more abundant access enjoyed

by Americans in other areas, even in states close to Montana. (Source: 105,

111)

Statistics relate the dearth of telephone service in Montana in

1907. Nationally, 1 of every 14.1

Americans had a telephone. The

comparable number in North Dakota was 1 in 14.2; even in mountainous Idaho the

number was 1 in 16.0. Montana lagged

36% behind the National number at 1 in 19.2. (Several Southern states recovering from the Civil War trailed

Montana.) The year 1907 would prove to

be the pinnacle year for Independents in America with about 50% of all

telephones being Independent. Although

the small farmer Independents in Montana had done an acceptable job, the truth

of the matter was neither Bell nor the Independents had deployed sufficient

capital: Montanans were underserved in

the new information age. Thaddeus Lane

was about to change this dynamic in 1907.

Within five years when 1 in 10.9 Americans would have a

telephone, the number in Montana would be 1 in 11.3, a difference of less

than 4% from the National number.

Much of this rapid positive enhancement in telephone service access and

more advanced telephony in Montana was attributable to Mr. Lane and his

competitive Independent companies.

These changes within the span of just five years aptly would be

described with superlatives: the work of “genius”. (Sources: 5, 23, 70)

Independent’s Day,

Butte

When on September 16, 1907 the Montana Independent Telephone

Company made operational its beautiful new three story exchange building at 124

West Granite Street in Butte, its rates and the RMBC rates were as follows per

year: For one party residential—MITC

$36, RMBC $42; for one party business—MITC $72, RMBC $80; and, for two party

business—MITC $54, RMBC $72.

Approximate numbers of telephones were:

MITC 225, RMBC 2,200. Within

three years, these numbers would be:

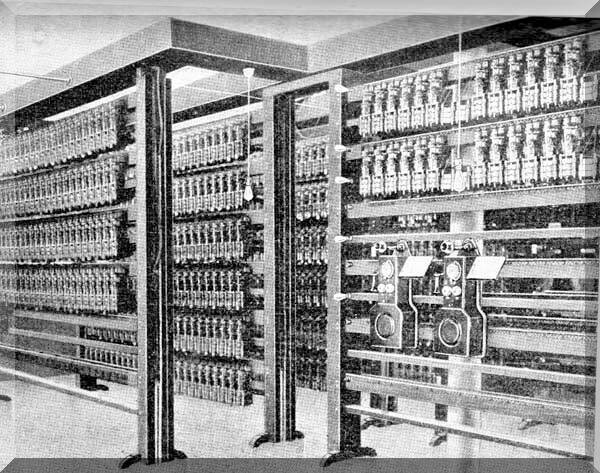

MITC 4,750 (an increase of over 2,100%), RMBC 1,500 (a decrease of 40%).

(Pictured below is an early MITC ad from just before September 16.) (Sources: 12A, 12C, 104, 109)

The exchange featured equipment supplied by the Automatic Electric

Company (AEC) of Chicago, the leading and enduring Strowger automatic switch

provider, which also financed Lane to some degree. The AEC advertised its facilities, if installed in a city of

100,000 people, would save 1/3, or about $67,000, in construction costs vs. a

manual cord board system, and also would save 40% in operating costs each year,

due in part to elimination of most operators. (Sources: 25A, 25B, Network

Nation p. 356)

Other features of the exchange were the duplicity of important

equipment, alarms and light sensors for trouble alerts and 100,000 feet of

underground conduits for main circuits.

(A somewhat dilatory issue affecting RMBC customer additions was its

more extensive use of overhead wire on poles; these were unsightly and placed

constraints on new customer numbers.)

Manhole #1 in the basement of the MITC exchange was 6’ x 7’ with

twenty-eight ducts each able to handle 400 customers. MITC private branch exchanges, or PBX’s, were installed at the

Anaconda Mining Company and Hennessy Mercantile Company, with other large businesses

in the order queue for their own PBX systems.

(Source: 12A) (Link to Footnote F) F1

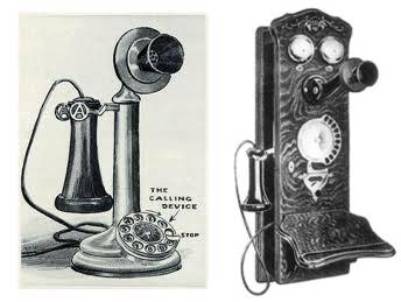

The standard MITC dial telephone was nickel plated, with black and oak models available; their deployment required public education. The following instruction was featured in an advertisement announcing the opening of a typical Lane automatic exchange: “The instruments have the general appearance of the old style manual telephone, with the exception that the small dial is installed in the base of the instrument. The subscriber connects with the telephone desired with three or four pulls of the dial, the ringing signal being given automatically without effort on the part of the subscriber.” The ad continued by describing how to dial the telephone number “650”. Independent company publicity included open house showings at new exchange buildings so as to showcase the inner workings of the automatic equipment. (Pictured below are two models of AEC dial telephones from the period.) (Source: “The Treasure State”, December 18, 1909, Montana Historical Society)

Butte’s population of about 86,000 and its substantial industrial

and business base afforded MITC an excellent chance to sell the community on

the advantages of modern, automatic dial telephone service. It did so by offering a free service trail

for a month or two to every Bell subscriber who expressed interest in MITC

service. Nearly 900 telephones were at

customer locations on the day the exchange opened, with 225 connected. Some customers had dual service with RMBC

and MITC. Nearly 3,000 telephones had

been placed within six months, a number nearly 40% higher than Bell’s installed

base after doing business for twenty-five years in Butte. Success seemed to be

assured. (Sources: 12A, 12B, 21, 22)

(Link to Footnote G) G1

The new exchange launched Butte into the next chapter of the

budding information age, financed largely if not completely with “Montana

capital”. This included more than 400

Montana investors statewide “representing nearly every large interest in the

state, as well as every trade and profession”.

(By comparison, there were just 24 RMBC stockholders in its Montana

service territory in late 1906.) Investing

in a local Independent company apparently appealed to a wide swath of Montanans. Within another 2 ½ years the number would be

nearly 2,000. (Sources: 9, 12A) (Link

to Footnote H) H1

Independents’

Days, Montana

As Lane built out his Independent system in Montana and

westward over the next few years, accounts suggest that he was

exceptionally capable in his ability to build a shared vision among investors,

customers and employees. Recall while

in New York he had parlayed his telephone activities to encompass forty-two exchanges

in just a few years. These same but

even more finely honed skills in Montana were heartily appreciated. For example, the Helena based and

unaffiliated “The Treasure State” magazine would extol upon his “invaluable

faculty of radiating local confidence, inspiriting dejected enterprise,

restoring self-confidence in others and urging forward the rapid economic

success of all his undertakings.”

Visionaries, technologists and promoters in Lane’s day and forward,

including those operating within the present day of information age technology,

may understandably relate to Lane’s skills as he ensured through his

sophisticated maneuverings that the most up-to-date technology at reasonable

prices would be available to customers.

(Source: 5)

Without going too far afield, it is important here to consider the

cultural shift occurring at this time in Montana. Early 20th century Montana witnessed a spirit akin to that of

manifest destiny; its optimism spurred the development of what had been

pioneered just a few years preceding.

Good and growing rail transport was prospering. Large corporate mining and timber

development were in full swing. The

small farm homestead boom with its irrigation projects and the damming of the

mighty Missouri waterway to provide long distance electricity were ready to

launch. Recollections of the bison,

open range and original pioneers were etched into the Montana psyche as

remnants from the tough frontier, but the 20th century was shoving aside these

recollections with its new opportunities of airplane experimentation, mass

automobile production, longer distance telecommunications, moving pictures, the

phonograph, deForest’s radio broadcasts and even Einstein’s theoretical physics

of relativity. Seemingly frivolous

inventions of the period would contribute to convenience and the soon-to-come

age of consumerism: the coat hanger, crayons, Popsicle, paper towels,

cellophane, life savers, the zipper, the shopping bag and a board game that

later would be named Monopoly. Thaddeus Lane, born of the generation

following the Civil War, had watched the physical westward line of the frontier

disappear. But a new and rapidly

expanding technological frontier arising as the next phoenix was ready for the

entrepreneurial taking with few restrictions, if one desired to pull at its

brass ring. Thaddeus Lane would give it

a good hard pull indeed, helping Montanans to spread their technological wings

during this period and catch a glimpse, albeit partially fleeting, of the

future.

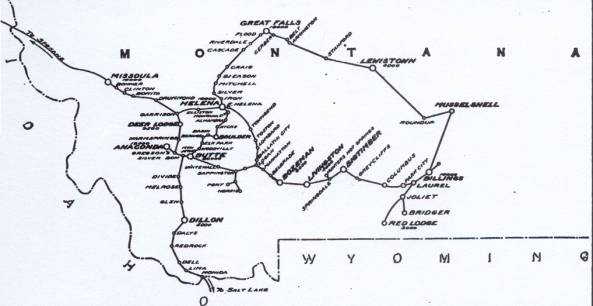

The “good hard pull” was manifested in the map of the Lane system

of telephone companies published by Telephone Securities Weekly a couple of

years after the Butte exchange opened showed an extensive system extending

north from Butte to Helena and Great Falls, thence north to Conrad, thence from

Great Falls east and south to Lewistown, Roundup, Billings and Red Lodge, thence

west from Billings through Livingston and Bozeman. From Butte west it shows Anaconda, Deer Lodge, Missoula, thence

south to Hamilton; from Missoula thence north and west to Coeur d’Alene,

Spokane, Sand Point and thence back east to Thompson Falls; from Spokane thence

south and west as far as Pendleton, Or and Lewiston, Id. A total of forty-nine local exchanges and

many toll offices were depicted.

(Pictures below are: a 1907 Montana

system planning map; the Helena exchange subsequently modified with a second

story; and, a circa 1911 Helena exchange telephone directory.) (Source: 9) (Read about technical and other

features of the Lane system at this link: Lane

Automatic System Sidebar) LSS

|

|

|

Local exchange and combination local/toll companies of which Lane

was president by this time included separate Automatic Companies in Helena and

Great Falls, the Billings Mutual Telephone Company, the MITC at Butte,

Anaconda, Missoula and Hamilton, the State Telephone and Telegraph Company at

Bozeman and Livingston, the Interstate Telephone Company Limited at Coeur

d’Alene, Sandpoint and Panhandle, the Idaho Independent Telephone Company at

Pocatello, and the Home Telephone and Telegraph Company at Spokane. Finally, there is one more Lane company to

seriously consider, it being of supreme importance in this unraveling

tale: A holding company called the

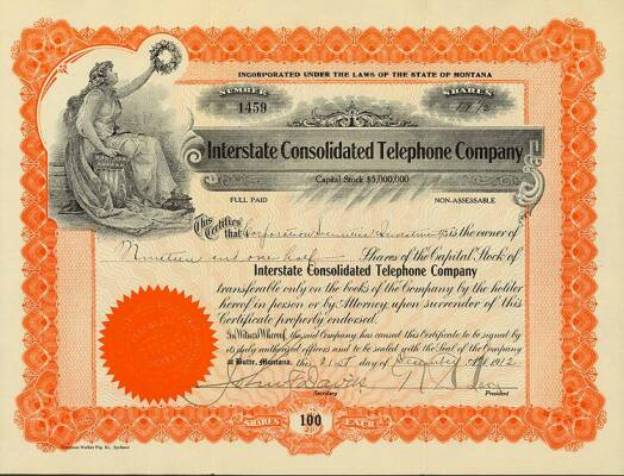

Interstate Consolidated Telephone Company (ICTC). (Source: 9)

The genesis of ICTC’s formation as an overarching holding

company that would own all of the other companies listed above was detailed in

five carefully written pages a few years earlier on December 13, 1908, Lane to

A.B. Cook, as follows: William Mead, a

Los Angeles capitalist and high flyer, was pursuing Lane to invest heavily in

the Home Telephone and Telegraph Company of Spokane, an Independent

company. (Recall Lane had considered it

in conjunction with his westward reaching long distance toll system plans.) It

had incorporated in 1906 and contracted with Empire Construction Company of Los

Angeles to build an exchange and underground lines; construction had begun by

December 1906. In September 1907 the

journal Telephony issued an exposé alleging the Kellogg Company, whose

switching equipment had been used by Empire (and others), was controlled by the

Bell system, and that this equipment would be used to undermine completed

Independent company facilities. Mead’s

National Securities Company of Los Angeles was involved in financing Spokane,

with nearly $350,000 spent for an unfinished exchange on Howard Street and

200,000 feet of underground conduit. Mead wanted Lane to invest and finish the

languishing construction. Lane’s letter

to Cook listed a Byzantine arrangement of financing, alliances,

responsibilities and optimistic completion dates. It is his first known salvo initiating the Spokane affair. Eventually it would be Lane’s nadir and

would lead to the undoing of his progressive Montana Independent company

telephone network.

Following up the letter to

Cook, Lane persisted with another even more detailed letter to another director

in May 1909, Lane to John MacGinniss.

In it he specified how ICTC would acquire the stock of all the other

Lane companies, how the corporate structure would be patterned after the Bell

octopus model by separating long distance toll facilities from local exchange

companies so as to realize higher returns on investment, how centralized

financing could be accomplished by ICTC and very importantly, how this

financing could be designed to make better use of a favorite Lane financing

device, that being watered bonus common stock used to entice potential

preferred stock and bond holders, salesmen and underwriters. (Sources: 13A, 31D)

Most importantly of all in the letter, Lane clearly declared his

over-riding goal, a seemingly incongruous goal given his theretofore

rock-solid reputation in Independent company telephony. He was proposing ICTC as a vehicle to

facilitate the eventual sale of all the Lane-centric properties to Bell

because of “unusual profit possibilities”.

He specified that the holding company would have “a property and

territory which the Bell Company must eventually acquire, unless it

wishes to entirely abandon Montana, Idaho and Eastern Washington, which is not

at all probable.” He surmised that the

older RMBC facilities and operations would be wound down so that Bell could

“endeavor to hold the field by acquiring the various Independent properties in

the Rocky Mountain territory, which have taken the business and have the

advantage of superior construction, equipment and public sentiment.” He continued: “In this connection, the fact that we will have an absolute

monopoly of automatic telephone equipment in our territory, should not be

overlooked, as it is one of our strong assets.” He punctuated the letter’s end by explaining plans for telegraph

service on his telephone lines, as well as his pressing desire to enter

the Spokane market. (Source: 31D)

The ICTC was breathed to life on October 21, 1909 as the holding

company for all of the other Lane companies; its authorized capitalization was

$5,000,000. Directors within a few

months after incorporation included:

Lane; T.I Greenough, capitalist,

Missoula; A.B. Cook and John MacGinniss, Patrick Wall, attorney, Butte; and, William Mead, National Securities

Company of Los Angeles. Others were

interested as well, including John F. Davies, a Butte attorney, who would

become Secretary. (Pictured below is

an ICTC stock certificate; the owner was Corporation Securities and Investment

Company.) (Sources: 26, 26A, 112)

Formation of the ICTC holding company marked a bright line

transition in Lane’s strategy and the Independent company movement in

Montana. He realized that a single

point of ownership would be highly advantageous if the telephone operations

eventually were to be sold, which was his new goal. Balanced against holding company goals and a corporate headquarters

relocated to Spokane, was the public relations challenge of at least appearing

to be a local Independent operation in the somewhat profitable Montana communities

that gave him his start in the West.

They had, after all, heartily embraced the idea of goodwill, financial

support and local ownership.

Once again, Latzke’s “Fight With An Octopus” was relevant. A chapter familiar to Lane and Montanans,

“The Fate of a Traitor”, discussed Independent company sales to the Bell

octopus: “It is probably difficult for

the ordinary businessman to understand why a person should not have the right,

unchallenged, to sell his property as he pleases, even if that property

consists of a majority of the stock of an Independent telephone company, which

can be turned over to the Bell at a fancy figure. But to the men in this

movement the moral wrong of such a transaction is as plain as day; they would

as soon concede that Benedict Arnold had a right to sell out to the

British. Nor does their argument lack

force or logic. They insist that, when

a man or a body of men organizes an Independent telephone company it is not

only the money paid in for apparatus and equipment that is capitalized, but the

goodwill, support, and friendship of their neighbors as well.”

This populist/progressive sentiment especially was keen in Butte

where Lane sorely needed to maintain local confidence; it above all was his

foundation. A good example of his endeavors

in this direction was the message to customers and investors in March 1910 when

he addressed in writing the “vicious” tactics of Bell, spoke of MITC’s good

earnings, and rose to the bully pulpit in praising the local ownership of the Montana

Independent Telephone Company (MITC).

(Source: 27)

Spokane Becomes

The Primary Focus

Irregardless, at least a few minority stockholders in Butte,

perhaps under Rocky Mountain Bell Company (RMBC) guidance, were becoming

suspicious; they provided a detailed, sophisticated written notice of

complaints regarding Lane’s modus operandi and called for a meeting of

stockholders in the courtroom of a local District Court Judge. As Butte public opinion clouds were building

in 1910, Lane moved his residence from Butte to Spokane. (Source: 28)

Just after his move in the fiscal year ended in April 1911,

Montana operations appeared to be performing acceptably: MITC gross revenues were $218,998.45,

expenses were $178,642.61, which

included bond interest but not plant depreciation, and net earnings were

$40,355.84. MITC telephone numbers had increased

during the year by 2,095 to 7,278 as follows: Butte 4,880; Anaconda 534;

Missoula 1,102; Three Forks 95; Deer Lodge 243; Stevensville 107; Basin 22;

Logan 27; Drummond 48; Boulder 68; and, the brand new exchange at Hamilton 152. Service innovation included a wake up call

service, at least in Butte. If any of

the 400 patrons subscribing to it did not answer within ten minutes of the time

they designated to receive their call, a messenger was dispatched. Revolving work shifts at the mines may explain

the popularity of this innovative-for-the-times service. (Sources: 29, 62A)

Telephone statistics for other Lane properties, such as the

Helena, Great Falls or Billings companies would be shown in their own

respective company reports. Suffice it

to say, Independent telephone numbers in Butte were more than five times those

of RMBC, Great Falls was three to one and Helena was equal. The Montana local exchange and long

distance toll system operated in abstentia of Spokane likely would have

prospered, especially if appropriate RMBC interconnection could be utilized, as

provided by Montana law. Spokane,

however, would be a horse of a different color. (Sources: 30, 83, comparison of telephone company directories for

Helena numbers)

After the Howard street exchange became operational in Spokane,

significant sums (see next paragraph) would need to be expended during later

1910, 1911 and into 1912 to make the Spokane operations viably

competitive. Most immediately pressing

was the need to actually start providing service to at least 4,000 customers before

any revenues at all could be collected, per the franchise. Lane predicted 15,000 SHTC telephones, then

30,000; but only 3,000 had been placed as of April 1911; this meant no

meaningful revenue, and a plethora of expenses accumulating since October

1909. To build-out the operational

capabilities of the system, he constructed a large main office exchange, the

Roosevelt Exchange (former President Theodore Roosevelt ceremonially assisted

in making operational the Roosevelt automatic exchange in April 1911, the

largest in the ICTC system with a 100,000 line potential), another exchange at

Hillyard, as well as several smaller exchanges/sub-exchanges. Also he rebuilt some of the facilities

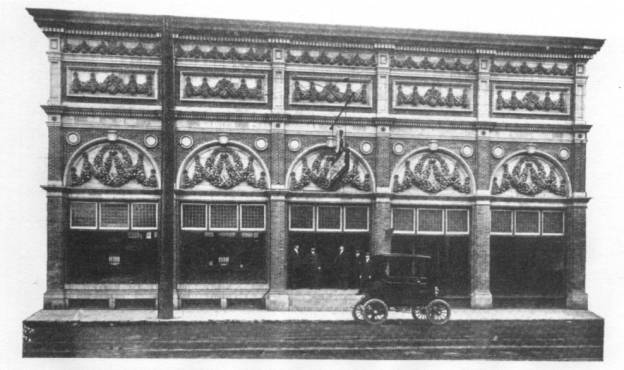

poorly constructed by the Empire Construction Company. (The Roosevelt exchange building is pictured

below.) (Sources: 30, 31A, 31B, 31C,

31D, 31E)

To provide long distance toll service between the Interstate

Consolidated Telephone Company (ICTC) systems in Montana and those to the west,

the company was extending its toll infrastructure through the “wilderness”

terrain west of Missoula through Mullan, Idaho. Not even the Bell system had successfully traversed this

terrain. (The first major Bell long

distance line through this area would wait until the mid 1920’s when the

Northern Transcontinental toll line was completed.) To the west, Spokane to Seattle, Lane had arranged to lease lines

from the Postal Telegraph Company, which was making a valiant attempt to form

alliances with Independent companies across America so as to combat the

ATT-Western Union combination. (ATT had

purchased a controlling interest in Western Union in 1909, a highly incendiary

decision long contemplated by Bell.)

The roughly $1,000,000 needed for the Spokane local exchange build out

and toll facilities east and west of Spokane, all within a 1¾ years timeframe,

would stretch ICTC financing needs beyond its capabilities. (Sources: 22, 31D, 32A, 32B, 32C)

Financial Stress

Lane found himself in a classic capital squeeze: Adequate and reasonably priced financing was

needed to build large facilities in a larger market in which demand was

increasing, but would remain muted until a viable build-out was completed. Layered on was a long-tenured, entrenched

and larger Bell company competitor and the financially debilitating

provision in the Spokane franchise requiring free service until 4,000 customers

were connected. (Source: 31B)

Adding uncertainty to ICTC

plans was the provision in its Spokane franchise allowing the city to purchase

ICTC facilities. Perception amongst

potential financiers of this possibility would have been palpable; voters in

Seattle passed by more than a 3 to 2 margin in November 1911 an initiative to

purchase “its” local Independent telephone company. (Great Falls citizens also were monitoring the Seattle

initiative.) One important factor

working to ICTC’s advantage, if it could find financing over the ensuing couple

of years, was the expiration in 1914 of the Bell company’s Spokane

franchise. (Sources: 63A, 63B, 82)

Coincident with Lane’s telephone activities in Spokane was another

newly undertaken endeavor with the potential to backstop the stressed financial

needs of the telephone empire. Involved

in it with Lane were familiar cronies MacGinniss, Cook and others; Lane was

president/vice-president, while Cook/MacGinniss were directors. Together they had had become officers/directors

on the bully pulpit for a fire insurance company in Spokane, the Western Empire

Insurance Company, and a newly formed life insurance company in Montana, the

National Life Insurance Company. The

companies appeared to be financially solid per their year-end 1911 annual

reports to shareholders and the Washington insurance regulator. (Sources: 33A, 33B)

A June 6, 1911 letter, Lane to Cook, exemplifies the close

relationship between the telephone companies and the insurance companies as it

memorializes Cook’s trade of $18,000 of telephone company bonds of the Helena

Automatic, the Idaho Independent and the State Telephone, for 216 shares of Western

Empire Insurance Company stock.

MacGinniss made exactly the same trade per an August 4th

letter. The Cook/MacGinniss telephone

company bonds were traded at par value, while the insurance company

stock value was discounted seventeen percent. What occurred in the context of the significant financial stress

and perhaps receivership concerns at the Lane telephone companies was: at the very least, unethical individual risk

mitigation by insiders; or, even more egregious if the insurance company shares

were quickly sold on the open market, a subterfuge to transfer $30,000. into

struggling telephone company financial needs.

Policy owners and small investors sold on the value of local insurance

company patronization would have been clueless to these tactics affecting the

stability of their insurance company investments and products. (Sources: 33, 33C)

As the 1911 calendar ticked away, Lane juggled the significant

telephone financing needs from many angles, including offering his personal

assets as collateral. Two money sources

to which ICTC became more and more indebted were Willaim Mead, and the Automtic

Electric Company (AEC). Smaller

creditors, like The Exchange National Bank of Spokane, were tightening the

noose on co-signors of ICTC notes. The

bank’s August 31 letter to Cook demanded payment: “Please take notice that the note of $25,000 signed by the

Interstate Consolidated Telephone Company, dated March 11-11 and due July

11-11, with interest at eight per cent, is past due and unpaid. Repeated demands upon the Telephone Company

have failed to bring results. We

therefore look to you for the payment of the same.” (Sources: 25B, 34A, 34B, 34C)

A Giant Awakens

Contra to Lane’s troubles, the Bell system was firming up

its strategies during the last half of 1911 so as to advance its telephone

industry coup-de-grace combination of ATT and Western Union. In August it offered the first large

underwriting for the Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph company (MSTT),

which combined the assets of the following companies: Colorado Telephone

(Colorado, New Mexico), Rocky Mountain Bell Telephone (Utah, Idaho, Montana,

Wyoming) and Tri-State Telephone and Telegraph (Arizona, southern New Mexico,

El Paso County Texas). Pacific states’

operations remained with Pacific Telephone and Telegraph. The prospectus made particular note of MSTT

financial strength. (Source: 35A)

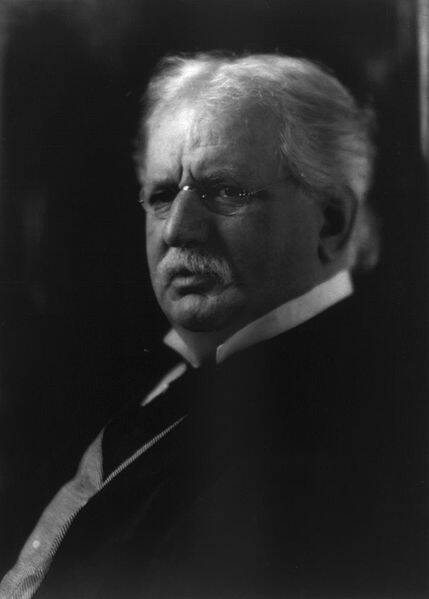

Near years end, Lane was attempting to arrange a hail-mary sale of

securities in the east to cover unpaid bills, and most importantly, to pay bond

interest expense coming due in November.

Unpaid bond obligations could force ICTC into receivership. Coincident with Lane’s financing trip to the

east coast in late 1911 was a pronouncement made in the Spokane Chronicle by

ATT president Theodore Vail that “as soon as the people demand it, the Bell

company will purchase the various competing telephone systems now operating in

the northwest.” (Theodore Vail is

pictured below.) (Sources: 36A, 36B)

Vail’s most conspicuous

previous attempt to buy or merge with the Independents came a year earlier when

a committee of seven leading Independent company representatives were appointed

by the Independent Telephone Association at a Chicago meeting. The seven

independent representatives, who met with Vail and a representative of ATT

owner J.P. Morgan (J.P. Morgan had acquired a controlling interest in ATT in

1907 and reinstalled a favorite son, that being Theodore Vail, who had left

Bell employment a couple of decades earlier), were treated to Vail at his

finest as he specified “the public had profited up to that time by destructive

competition, but that once the merger was formed, the company was going to make

the public pay for it.” Vail proposed a

$1.3 billion ($31.8 billion in 2011 dollars) merger at the meeting to take

place over several years with multitudes of Independent companies to be merged

and acquired. The Chicago meeting ended

without result, but the seed and strategy had been launched. (Sources: 37A, 37B, Network Nation pp. 312,

346-47, www.measuringworth.com)

Lane did acquire financing for the Interstate Consolidated

Telephone Company (ICTC) in the east from a German investment bank MacGinniss

had used when arranging Heintze financing, that being Hallgarten. The financing, at fire sale terms, procured

$150,000 by giving Hallgarten $190,000 in MITC bonds and the same amount of its

common stock as a bonus. It presaged

what could become a death knell scenario, using Montana operations as

collateral to shore-up Spokane.

Ironically while in the east, Lane also responded to Vail that the

Spokane Home Telephone company was not for sale. The response came through his talented publicity director, Byron

E. Cooney, who later would become a popular union-supported state legislator

from Butte. (His brother was future

Montana Governor Frank Cooney, 1933-35.)

(Sources: 38A, 38B, 84, 107)

Lane’s response, in his usual “generous and freehanded way”,

listed the alliance by Independent companies with the Postal Telegraph Company

to compete with Bell and the financial infusion by large international bankers

into securities of Independents in the northwest as factors that accounted “for Mr. Vail’s appearance at this time and

his frequently expressed desire to be permitted to operate without

competition.” In the response, he

raised the Butte operations as a model of modern automatic telephony. At the very time of his response, interests,

directly and indirectly controlled by Bell, would have been able to force ICTC

into receivership if the November 1911 bond interest had not been paid--and the

May 1912 payments soon would be due. In

effect then, Lane’s response largely was blustery publicity. (Sources: 34B, 36B, 38A, 39A)

The ICTC financial situation

was not unique in the Pacific Northwest.

Vail’s purchase offer was a broad one, and various companies appeared to

be financially stressed, or in receivership.

Such was the case with a there-to-for moderately successful toll company

in the Seattle area, The Northwestern Long Distance Telephone Company. Bell interests had engaged in several

strategic moves, leaving Northwestern high and dry of much of its business. Added to this were the usual Bell secretive

manipulations, some of which were exposed thusly in early 1912: A minority stockholder, who with William

Mead had been one of the original incorporators and directors of the National

Securities Company of Los Angeles, alleged that his former associate Mead,

through a title company he owned and which owned many of the bonds of

Northwestern, had conspired to force Northwestern into receivership so as to

acquire the property at a bargain price for Bell interests. This expose was the first public revelation

of William Mead’s real motives in deals he had been making in the northwest,

like that made with Lane in Spokane.

(Sources: 40A, 40B)

An End Game

Nearly coincident with Vail’s offer to purchase properties in the

Pacific Northwest was the formation in Great Falls of a committee to

investigate consolidation of Bell and Great Falls Automatic. (The city had supported a Bell competitor a

dozen years prior, The Dunlap Telephone Company, until Bell purchased it.) Questionnaires were sent to the two

companies under the signature of Chairman F.A. Fligman. Responses made it clear that neither party

wanted to sell to the other, but each would purchase the other under conditions

specified in its response. At a January

11, 1912 committee meeting attended by Lane and Bell representative H.P. Story,

intermarrying telephone competitors was discussed, with committee member

Herbert Strain reporting that Governor Norris, when querried by him, specified

that such a merger or purchase was illegal.

The ever-sharp Lane then introduced another “rather startling

proposition”: Great Falls Automatic

would agree physically to interconnect with Bell. The meeting ended without

result, but within 24 hours both the Great Falls Tribune and the committee

concurred with Lane’s offer, with the Tribune calling the proposal

“revolutionary”. The Tribune editorial

specified: “Inasmuch as the Automatic

company has a considerably larger number of subscribers in its Great Falls

exchange than the old company, its offer cannot be considered otherwise than

fair…”. Lane’s overture was tantamount

to a very public request, a dare if you will, to MSTT to interconnect per Judge

Hunt’s decision and the Montana constitution.

The Tribune Editorial referenced the Hunt decision. Lane’s bravado would serve him well, given

his tough financial situation; it had painted Bell into somewhat of a

corner. (Sources: 81, 89, 90, 91)

Within in few weeks,

MacGinniss and Lane traveled to Denver, on the one hand in a sort of grovel to

Vail’s financing and purchase overtures, and on the other hand, in a position

of some strength gained from what had happened in Great Falls. The trip was on the sly, although Cook

partially was privy. Although a sale

had been in the scheming since 1909, the cash strapped ICTC didn’t appear financially

to be very desirable in its nearly busted condition. Involved in the negotiations were the son of MSTT’s president and

corporate counsel Milton Smith. The

discussions resulted in a surreptitious contract whereby MSTT would purchase a

controlling interest in ICTC via a newly minted MSTT subsidiary---incorporated

on the same day as the purchase/sale agreement on February 3, 1912. The entity was named Corporation Securities

and Investment Company; its three directors were stenographers, two of them (M.

Stewart, President and H.C. Davidson, Secretary/Treasurer) in the employ of

MSTT. (Pictured below is a cartoon

showing a potential Bell payoff.)

(Sources: 38A, 39A, 41A, 108)

The illicit purchase was an arrogant abrogation of the clear intent

of Montana’s constitution, section 14, article 15: “No telegraph or telephone company shall consolidate with, or hold

a controlling interest in the stock or bonds of any other telegraph or

telephone company owning or having control of competing lines of

telegraph or telephone.” Montana’s

statute section 4402 included the exact same language, but no penalty clause.

(A penalty potentially of concern to Bell was possible revocation of its

Montana corporate charter.) The nexus between

Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph (MSTT) and each of Lane’s five Montana

companies competing with MSTT was hard to miss: MSTT clearly owned/controlled

the Corporation Securities Investment Company and the Interstate Consolidated

Telephone Company (ICTC) clearly owned/controlled Lane’s Montana

companies. MSTT’s formation of the narrowly

construed Corporation Securities and Investment Company was legal shenanigry

parading in its finest illegal attire. (Source: 83)

The controlling interest purchase of 17,555 shares was

accomplished very quickly at $82.85/share, a spectacular price unfathomable

under rational economic calculus, save that of a well-healed quasi monopolist

on a mission. The total amount paid to

Lane and MacGinniss was $1,454,400. The

shares largely would have been bonus stock in which these two men had invested

little or no money. Lane and MacGinniss

over the next six years helped to acquire the remaining securities of minority

interests of the Lane companies.

Questionable tactics sometimes were used, with a few sellers alleging in

legal actions that fraudulent tactics were used. The tactics were of some embarrassment to MSTT, since the purchase/sale

agreement clearly specified the average prices it would pay for the securities.

(Sources: 38A, 41A, 101)

At the time of the Lane/MacGinniss

sale to MSTT, ICTC’s book value was about $13/share with the stock trading on

the Spokane market at between $12-$20/share.

The price realized by Lane/MacGinniss from MSTT on subsequently acquired

shares is not known with certainty; in court proceedings spanning more than the

next decade, MacGinniss simply specified that they realized a variety of prices

for the shares. It safely can be stated

that many minority shares were purchased by the two men at between $20 and $50

share, knowing that they would sell the same to MSTT at $70/share per the

sales/purchase agreement. Be that as it

may be, in real dollars terms a century later in 2011, just the original profit

of $1,454,400 is equal to a CPI adjusted $34,800,000, and this profit was

realized in advance of income tax requirements enacted in 1913. Additionally, the bonds these men commandeered

previously at substantial discounts immediately would have been worth 100% of

face value, an event worth another fortune. (Sources: 38A, 41A, 101, 102,

www.measuringworth.com) (Link to Footnote I) I1

Lane danced on a tightrope in Spokane as word of his Denver trip

started leaking. A chief concern was

the franchise for the Spokane Home telephone company, which prohibited its sale

to a rival concern, i.e. Bell interests.

The January 13, 1913 Spokesman-Review reported Lane refuting rumors and

detrimental talk regarding Spokane Home, specifying these were circulated by a

few disgruntled stockholders and that the company was in excellent shape: “It is true the company owed a lot of money

some months ago, but the sale of the Great Falls plant wiped that out and the

company now is in a good condition. There

is absolutely nothing to the report that the Bell will buy out the Home company

in Spokane.” The article also

referred to the sale of the Helena plant.

His scheme was catching up with him, but in the end Lane would slip like

teflon through this web of deceit.

The Federal Government

Awakens Briefly; Montana's State Government Dozes

One office that should have been noticing changes in ownership of

Great Falls and Helena telephone companies was the ex officio Montana Public

Service Commission (PSC) of the Railroad Commission established in March 1913;

it was imbued by that Legislature with regulating all telephone provider rates

and services. Two years earlier,

Railroad Commissioner Edward E. Morely wrongly had predicted these duties would

be added by the 1911 Legislature:

“Personally, I favor the supervision and control by the commission of

the two enterprises just mentioned (telegraph and telephone), if for no other

reason than the fact that after the legislature has adjourned, in the

twenty-two months to follow, conditions may be such as to require our

services.” (Source: 42A)

Two months after its formation, the PSC sought an Attorney

General’s opinion regarding its powers to require consolidation with Bell of an

Independent company in the Hamilton area, known as the Bitter Root Valley

Telephone Company before MITC purchased it in the fall, 1909. Attorney General D.M. Kelly responded

immediately: The PSC couldn’t require

consolidation because Montana law comprehensively prohibited common ownership

or control of competing telephone companies.

He further opined that the companies could interconnect so that citizens

would be “relieved of the burden and cost of maintaining a double

service…”. If it weren’t already aware,

a coming national spectre soon would inform the PSC of the illicit MSTT/ICTC

combination affecting the Hamilton exchange.

Once informed, the Attorney General’s opinion could have assisted it in

setting the whole of the record straight, according to law. (Sources: 43A, 65) (Link to Footnote J) J1

Before newly elected

President Wilson was sworn into office early in 1913, the U.S. government had

begun an investigation into the telephone industry, but it had stalled during

the Taft presidency. The investigation

was renewed with vigor within a few weeks of the President’s inauguration in

March. Anti-trust activities in the

Pacific Northwest were a first priority on the radar screen of Attorney General

McReynolds and his special assistant, Constantine B. Smythe, who formerly was

an attorney general in a state in which public ownership of utilities

continuously has thrived into the current day, that being Nebraska. (Also in

March, J.P. Morgan died, thus ending a personal quest by ATT’s owner to control

the telephone industry.) (Sources: 40A,

44A, 53B, Network Nation pp. 351-353)

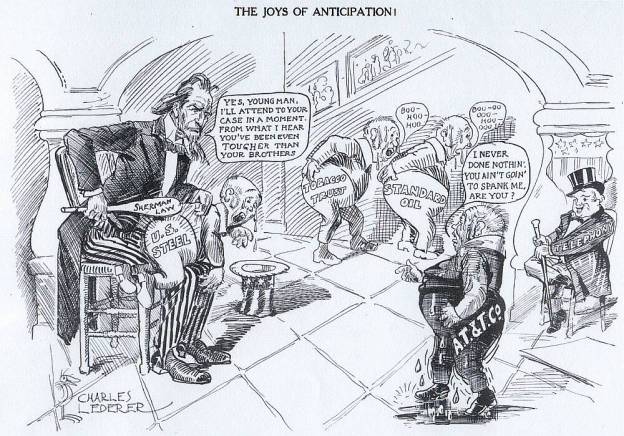

Just a few months later on July 24th the Justice Department filed

in Judge Robert S. Bean’s federal district court in Portland, Oregon its first

ever complaint against the Bell system under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of

1890, United States v. American Telephone and Telegraph Company. ICTC President Thaddeus Lane and Secretary

John Davies, and William Mead also were listed personally as defendants

in the action. The New York Times

reported in a “special” on July 25th:

“Among the independents mentioned are the Home Telephone Company of

Puget Sound, operating in Tacoma and Bellingham; the Independent Telephone

Company, operating in Seattle; the Interstate Consolidated Telephone Company,

operating in Montana, Idaho and Washington, and the Northwestern Long Distance

Telephone Company of Oregon and Washington.”

(Pictured below is a cartoon showing Uncle Sam “administering” the

Sherman Act.) (Sources: 44A, 45A)

The suit alleged the Bell system systematically had ruined

competitors by enticing them to break contracts, as well as providing below

cost or free service to drive competitors out of business, and by the outright

and systematic elimination of competition through purchase, including purchase

of 2/3’s of the common stock of the ICTC.

Smythe was quoted as saying:

“Today, through unlawful acts of this kind, all the local Independent

telephone companies of Washington, Idaho, Oregon and Montana--and there was an

Independent exchange in practically every city, town and village in these four

states—have been brought under the control of the Bell….” (Source: 46A)

He further opined that it wouldn’t surprise him if Bell admitted

its antitrust activities, using the defense that the telephone business was a

“natural monopoly”: “If the Bell wins

the present suit and its contentions for a ‘natural monopoly’ are declared in

accordance with law, it will have a free hand to go ahead and complete this

monopoly, by hook or by crook.” It was

his contention this defense should be defeated on its face because of a

paragraph in the Sherman Act forbidding any person “to monopolize or attempt to

monopolize or to combine or conspire with any other person to monopolize any

part of the trade between states or foreign nations”. (Source: 46A)

Anti Trust Stress

Test

Hearings over the next few months

were held in San Francisco, Tacoma, Portland, Seattle, Spokane, Butte, Denver,

Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York.

Smythe represented the United States, while Milton Smith, Denver, and

E.S. Pillsbury, San Francisco, represented Bell interests. Smith and Pillsbury were Bell

employees. Ironically in name, the

special examiner representing Judge Bean in these hearings was named Mary Bell.

Newspapers across Montana reported on the Spokane and Butte hearings,

showcasing the corruption and mismanagement by Lane and MSTT. (Sources: 37A, 39A, 47A, 83, 84, 85, 86, 97)

At the Butte hearing, P.B. Moss, who owned 2,670 shares of ICTC

stock or about 10% of the company, testified that Lane had waged a vigorous

campaign in the fall of 1912 to purchase ICTC stock, while he, Moss, had never

been informed of the deal with the Bell subsidiary, the Corporation Securities

and Investment Company. Bell attorney

Milton Smith was called under oath at the Denver hearing to explain the secret

anti-competitive Independent company purchasing activities of the Bell

subsidiary. At the Spokane hearing, E.S. Pillsbury alleged the antitrust suit

resulted from revenge indirectly perpetrated by Portland Home Telephone Company

owner, Samuel Hill, who was the son-in-law of Great Northern Railroad magnate

and Great Falls investor James J. Hill. (Source: 39A, 85)

As 1913 progressed, the once convivial relationships between

Lane/MacGinniss and other insiders deteriorated. A good example is demonstrated in a letter, MacGinniss to Cook,

explaining that P.B. Moss had retained the well know firm of Walsh, Nolan and

Scallon as legal counsel to settle their differences. In another letter, Cook to Lane, he stated: “I do not care who I do business with,

providing I get what I think I am entitled to for the securities.” A plethora of lawsuits eventually would be

filed by insiders, some of which were settled, while others were